A Partial History of the Eastern Siouan People

I am indebted to so many people who have helped me with this research project. The people at the www.saponitown.com/forum were very helpful. Without their help I would never have even started researching the Eastern Siouan Peoples. Despite their words, I always remained skeptical. I will always believe that to find the truth you HAVE TO BE skeptical of everything. Dr. Thomas Blumer made me believe that I really might be part Catawba. Forest Hazel's research was of great help. Dr. Richard Allen Carlson's research proved the Melungeons were of Saponi ancestry. And there are so many others to whom I want to say thank you, too many to name. Even people I have argued with constantly, have been a great help. I thank you all.

Please know to look at the maps just click on them, and they will get larger.

Please know to look at the maps just click on them, and they will get larger.

Map 1.

Please notice the location of

Chicora. On the previous page (6), Hudson says: . . . another

colonial venture was set in potion in 1521 when two ships dropped

anchor off the Atlantic coast of the Lower South. One of these ships

was owned by Lucas Vasquez de Ayllon, an official of Santo Domingo.

The Spaniards went ashore, where they had a friendly encounter with

the Indians, some of whom they persuaded to come out and visit their

ships. But when the Indians canoed out and climbed aboard, the

Spaniards promptly enslaved about sixty of them and sailed for Santo

Domingo (Frances Lopez de Gomara, Historia general de los Indias,

Madrid, 1932, vol. 1, pp. 89-90, translated in New American World: A

Documentary History of North America to 1612, ed. David B. Quinn, New

York, : Arno Press, 1979, vol. 1, p. 248.). One of the ships sank

en route, and most of the Indians on the other ships died, but at

least one of the Indians on the other ships survived, to be baptized

Francisco de Chicora. (Peter

Martyr, De Orbe Novo, ed. And trans. F. A. MacNutt (New York, 1912,

vol. 2, pp. 254-271.).

Francisco

later was taught Spanish, and returned to the Carolina coast with a

future expedition to colonize the lands for the Spanish. Of course he

escaped, went home, and there is no further mention of the Chicora.

But we do have a band of Eastern Siouan called the Shakora. Are these

the same as Chicora? Perhaps the Chicora fled the coast after the

Spanish enslaved some of their warriors, feeling it was safer in the

interior.

From viewing

map 6, it appears they fled upstream 150 or 200 miles, where they are

called Shakori by 1650. By 1700, per map 7, they are in relatively

the same location still called Shakori. We will hear more about them

later.

Map 2. Above is a map from 'The Juan Pardo Expedition, Hudson, page 24. It shows the route taken by De Soto, earlier. East and North of the line from Hymahi to Cofitachequi to Xuala to Guasili, we have the Eastern Siouan peoples. To the west of Cofaqui in the south to Chiaha to the north, we have the Muscogeean speaking peoples. The Cherokees will enter later and conquer the northern parts of the Creek (Muscogeean) territory, from Chiaha to Coosa. The word 'Coosa' is of Creek origin – these communities either are not Cherokee, or non-Cherokees provided the names of these communities.

There are

some interesting Eastern Siouan towns mentioned by both De Soto and

Pardo. We have Xuala, the origin of the Saura, and Cofitachiqui, a

town that awed the Spaniards. What the Spaniards called Xuala and

later Joara on the map of the Juan Pardo expedition below, turns out

to be one of the main bands of the Eastern Siouan tribes, and is

later called Saura/Cheraw. The Guaquiri/Guateree later move nearer

the Catawba and become known as Wateree.

Map 3. Above map, from The Juan Pardo Expedition, Hudson, page 24. It shows the route of his expedition. The line from Juara to Olamico. The 'mico' ending indicates a Muscogeean (Creek) origin to the name. Joara of Pardo's (1566-1567) expedition is the equivalent of Xuala from De Soto's (1539-1540) day. The English called these people Saura, which later became Cheraw. Pardo only went as far as just beyond Juara. Moyano made the advance further to the northwest, to Olamico.

Map 7 shows the Cheraw's/Saura's

on the Upper Dan about 1700. Unfortunately, they are not shown on map

6, dated about 1650. Map 8 shows some of the Indian movements

Tuscarora War, It shows the Saura/Cheraw south and east of the main

Catawba cities. They had left their cities on the Dan River in 1703.

Map

4.

Below is another map found in 'The Expeditions of Juan Pardo, Hudson'. Many towns listed are from the Spanish era, but the rivers were named later. The caption to the map below is self explanatory. The towns on the far western and far southern parts of the above map are Creek/Muscogeean in origin. Something to ponder – most of both the Siouan and Muscogeean towns the Spaniards listed had disappeared before English chroniclers rediscovered them. What had happened to them? Be thinking about that.

Below is another map found in 'The Expeditions of Juan Pardo, Hudson'. Many towns listed are from the Spanish era, but the rivers were named later. The caption to the map below is self explanatory. The towns on the far western and far southern parts of the above map are Creek/Muscogeean in origin. Something to ponder – most of both the Siouan and Muscogeean towns the Spaniards listed had disappeared before English chroniclers rediscovered them. What had happened to them? Be thinking about that.

Guatari is also of interest. In

Spanish, 'Gua' is pronounced as the English 'wa', and the Spanish 'i'

is pronounced like the English long 'e'. So Guateri should be

pronounced 'Wa-ta-ree'. Map 13 also shows the movements of the

Guateree/Wateree from/to 1670 when they flee to live near the

Catawba,where they remained until they vanished.

Also notice the towns of Yssa and

Yssa the lesser. This is identical to Esaw, Issa, Iswa, Yesa, Yesah,

and perhaps more spellings can be found. The Yssa and the Catawba are

the same people. Esaws are shown on maps 7 and 9. Map 10 show the

Esaw between the Catawba and Waxhaw. This map dates to about 1715,

after the Tuscarora War, yet before the Yamassee War.

Notice Gueca. Almost straight

south of Guateri. Is Gueca, with the 'c' having a mark under it. This

would be pronounced sort of like an 's' sound. The Spanish 'e' is

pronounced like the English long 'a' sound. Remember “Gu' is

pronounced like a 'w'. So 'Guaca' would be pronounced something similar to 'Wa-sa'. Later

in the same location we will find the Waxhaw Indian town. Likewise,

Guiomae might be pronounced Wimae.

Many of these Bands of these Eastern Siouan

Indians did not move for a hundred or more years, while others did.

It appears as though those moving, were escaping some threat. The

Northern bands as we shall see later, fled Eastwards to receive the

protection from the English. Others fled to be nearer the main body of the Catawba for the same

reason. At some point the Cherokee moved into some of the lands

where the Spaniards had first discovered Creek Indians. This

movement by the Cherokee was one reason the Saura fled eastward

Map

5.

Below is a map compiled from data

dating to about 1650. It was taken from page 10, 'The Catawba

Nation', by Charles Hudson. Notice the Wateree have moved further

south. Notice to the South of the Wateree are the Congaree Indians.

It was said of the Wateree and the Congaree, that they couldn't

understand each other. I have thought about that. How could this be?

But when we see that the Wateree were originally further north, and

the Congaree were one of the furthest south of the Siouans, were they

Siouan at all? Unfortunately, Hudson says of the Congaree and others

in 'The Southeastern Indians; For some of these cultures, such as

[Hudson names several cultures in the Southeast, including the

Congaree of South Carolina] we know little more than their names.

They were on the border between the Muscogeeans and Siouans. It is

known that the Yuchi/Euchee had a language that seemed like a

Siouan/Muscogeean hybrid. Perhaps so was the language of the

Congeree. Maybe their language was more closely associated with the

Muscogeean peoples, and for some reason politically, they chose to

associate more closely with the Siouans. I like this map because it

shows all the Eastern Sioans, from the Manahoac in the North to the

Sewee in the South. This is one of the few maps I have seen that also contains

the Northern Siouan Bands.

Map

6a.

Below is the John Oglesby/James Joseph Moxon map Commissioned by

order of the Lords Proprietor of [South] Carolina in 1673. I don't

know how well this will print out. It shows Monacan, and Mahook (also

called Manahoak) in the North. To their south is Sapon Nahison,

Akenatzy (Occoneechi), and Enock (Eno), and Sabor (?Shakori?). To the

east of these cities and across a river are the Tuscarora. To the

west near the mountains are the Saunae (?Shawnee?). West of the

mountains are the Rickohockans, a mysterious people of unknown origin

So we have several nations wedged together in a narrow space. In the

south are Watery, Sara, Wisack (Waxhaw).Map 6b.

The map below is compiled from information dating to about 1700 (map taken from The Indians New World, by James H. Merrell. It is captioned 'Carolina and Virginia. Colonial settlement distribution adapted by Herman R. Friis, A series of population maps of the Carolinas and the United States, 1625-1790, rev. ed., New York 1968. Drawn by Linda Merrell'). Notice most of the bands have not moved a great deal. Other that the Shakori having gone inland since Spanish times, and we see the Saponi have moved further south, most of the rest as in virtually the same place.

In “The Indians of North

Carolina and their Relations with the Settlers” by James Hall Rand,

the author names the sixteen Tuscarora cities before the Tuscarora

War. On page 8, he says of the

Tuscarora; They had the following sixteen important

villages: Haruta, Waqni, Contahnah, Anna Oaka, Conaugh Kari, Herooka,

Una Nauhan, Kentanuska, Chunaneets, Kenta, Eno,

Naurheghne, Oonossura, Tosneoc, Nanawharitse, Nursurooka.” Were

the Eno originally a band of the Tuscarora? They appear on the 1650

map in the same location as they are living in 1700. Where

the Eno are concerned, Rand was wrong, they were a Siouan people, not Tuscaroran. But we see we must test what we read, and not simply accept what is written.

The Shakori

lived in close proxemity to the Eno, Keeauwee, Occoneechi, and

Saxapahaw, between 1650 and 1700. By 1715 they are called the

'Chickanee' and have moved westward closer to the Catawba. Map 13

shows this movement closer to the Catawba, and calls them

'Shoccoree'. They could be the 'Sutterie' of map14, about 1725. I

haven't found them after that date. That means little, I haven't

checked very hard. Note the Saras and Tutelo have changed places, and

the Cherokee are where the Chiaha civilization was located in Spanish

days, one or two hundred years earlier..

The Saxapahaw

are also found with the Eno and Shakori on Map 7 (c. 1700), but they

are not found on map 6 (abt. 1657). According to this map, they are

living very close to the Tuscarora. According to map 8, Saxapahaw is

a Tuscarora village passed through by Barnwell and his Eastern Siouan

allies in the Tuscarora War of 1711. It was also passed through in

the second Tuscarora War according to map 9. Were Saxapahaw and Eno

actually Tuscarora towns? Map makers and historians and writers,

well – make mistakes. You just have to work through these things,

and maybe make mistakes, yourself. If (or more accurately 'when' ) I make

mistakes, I hope others will correct me. That's life. Map 12 shows the former Tuscarora lands, and they are empty of

inhabitants by 1725. Even the Eastern Siouan Bands that were nearby,

are no longer living in the area. This opened the land up for White

settlements. The Eno, the Saxapahaw, the Shakori, have all moved or

vanished. In attampting to find the Saxapahaw, we find them on map

16, the deer skin drawing by an Indian chief dated about 1725. It has

a small circle, smaller than the others, where the Saxapahaw are

mentioned living with the Catawba. No map of a later time frame that

I have found, mentions them after this date. I suspect these Saxapahaw might be the people mentioned by Carlson as being at the headwaters of the Flatt River by 1732, which is very close to the location of several state recognized Saponi Bands, today.

The Keyauewee

are on a map dated 1650 map near the Tuscarora. On the 1700 map (map

7) they have moved westwards and are near the Saponi, to the north of

the Catawba. Map 12, dated about 1720, has the Keeauwee on the Pee

Dee River with the Cheraw. As with the other Siouan bands from this

region, they disappear after that date. The Saponi were near

Salisbury, NC before moving to Fort Christanna, and returned there

about 1729. But the settlers were now pouring into the area, and it

wasn't the same upon their return.

Map

8. Tuscarora War

Below is a map of the route the

John Barnwell's troops too on their was to attack the Tuscarora. The

map was from page 36 of Catawba Nation, Treasures in History, by

Thomas J. Blumer. The Tuscarora War lasted from 1711-1713 and ended

in the utter destruction of the Tuscarora and Coree Indians.

There is another 'Middle Band' of

the Yesah Nation – the Saura. The Spaniards found them living in

Western North Carolina, and called them the Xualla (De Soto), or

Joara (Pardo). Map 7 has the Saura on the upper Dan River by 1700.

They were said to have left the Upper Dan in 1703. By the time of the

Tuscarora Wars of 1711-1713, they are on the Pee Dee River (map 8)

South and East of the main Catawba towns, and they took part in the

first, but not the second Tuscarora War (map 9). Map 12 still has the

Cheraw on the Pee Dee River in 1720. Many researchers say that the

modern Lumbee Indians are actually the last remnants of the Old

Cheraw. Map 14 shows the actual locations of Upper and Lower Saura

Towns on the Dan River before they were abandoned about 1703. About

this time frame many Eastern Siouan cities in the western parts of

Carolina and northern Virginia were abandoned as they removed

themselves eastwards and southwards. Why the decline? We will try to

answer this question, later.

On the deer skin map (map 15)

dated 1725 the Charra are one the bands living near the Catawba. On

the 1756 map (map 17) there it is, Charrow Town next to the Catawba.

There is no Charrow Town on map 16, dated about 1750. They seem to

have maintained an existence longer than many other bands. As I said,

many speculate that the Lumbee Indians are their descendants.

Map 9. Between the Tuscarora and Yamassee Wars

The above map shows the locations

of the Southern Bands of the Carolina Siouans about the year 1715.

This would be just after the massacre of the Tuscarora and Coree

Indians, yet just before the Yamassee War, a war during which many

Siouan bands would disappear, or or be so reduced in number they

would be soon forgotten. It is taken from page 186 of 'The Juan Pardo

Expedition', Charles Hudson.

Map 10

This map shows the routes taken

by the warriors and soldiers during the destruction of the Tuscarora

in the second Tuscarora War.

Map 11.

Map 11.

The map below is also about the

same timeframe, about 1715. Notice the Cherokees are near where the

Coosa Indians (Creek) had been 100 years earlier, according to

Spanish records. The lands of the Siouans are shrinking and they

aren't realizing it, it seems. It was taken from 'The Catawba

Indians, The People of the River', by Douglas Summers Brown, between

pages 32 and 33.

Map

12.From 'The Indians New World', by James H. Merrell, page 86, we have the map below. The historic time when the map was accurate is about 1720. Where the Yamassee once were are now 'the Settlement Indians'. From the Catawba peoples on the Catawba River to the Atlantic coast and the Waccamaws, are several small bands of Eastern Siouan peoples. Notice the Sewees, Santee, Cores and Yamassee and others have disappeared and the Tuscarora are much smaller. The Saponi are just west of the remnant of the Tuscarora. Clearly the Tuscarora and Yamassee Wars have taken a heavy toll on the local Indian populations. A vast area where the Tuscarora had once been is now vacant of people, and thus is opened up for White settlement. Most of the eastern Siouans had abandoned central and western Virginia, and this region as well, was opened up for White settlement.

Map 13.

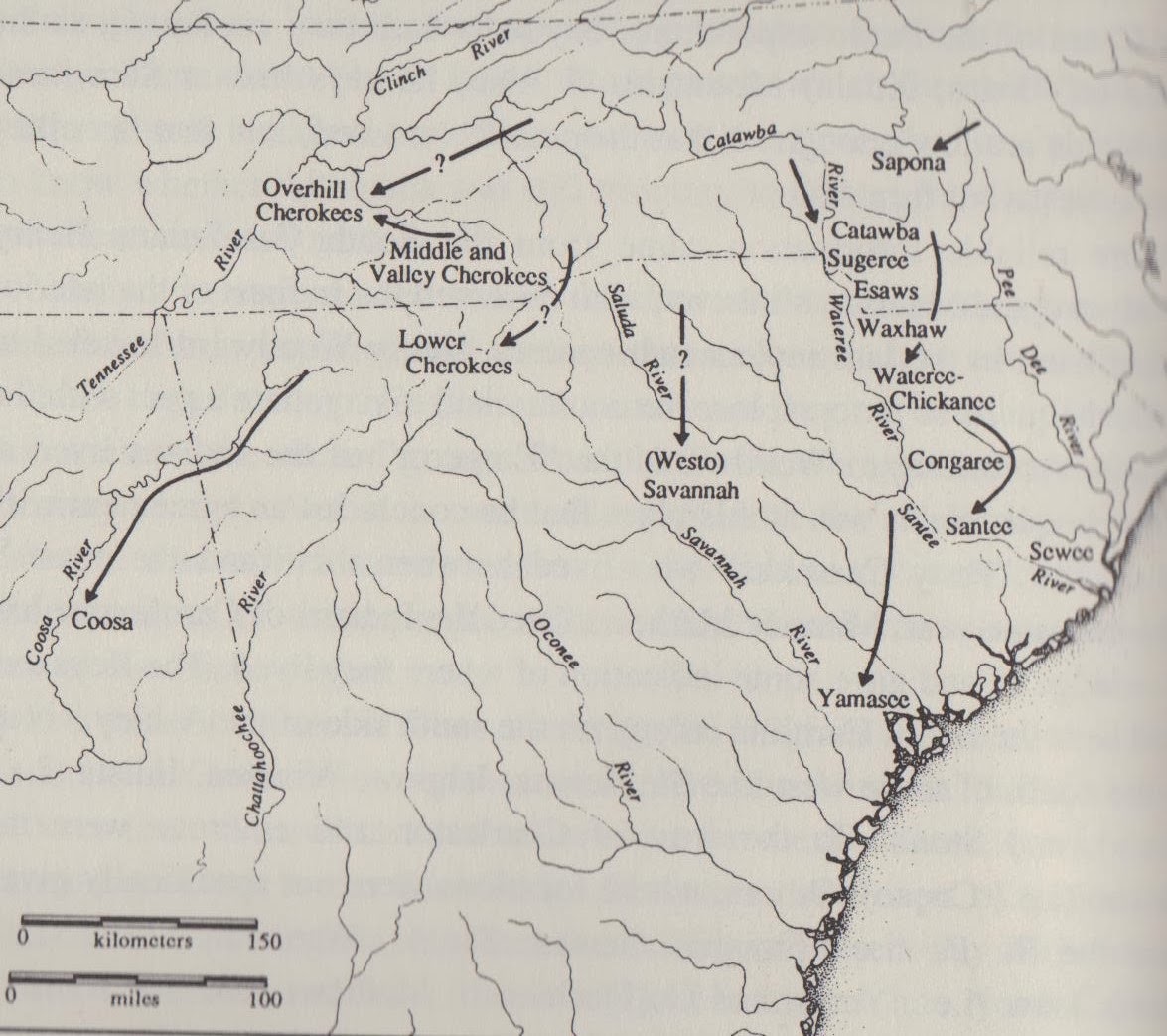

Below is a map showinig movements

of most of the Eastern Siouan groups between the times of De Soto and

Pardo Pardo to the middle of the 18th century, when many

groups disappear from most historical records. It is taken from

'Catawba and Neighboring Groups', by Blair A. Rudes, Thomas J.

Blumer, and J. Alan May, p. 302. This map does not show the movements

of the Northern branch of these Eastern Siouan groups.

These groups were moving i.]

towards the Catawba; or ii.] to be nearer Charleston. Both moves

appear to be for safety. They were afraid of something in the

interior. Was it just enemy Indians, or was it something more

sinister? Then during the Yamassee many turned on the English near

Charleston. Why? They were already very weak before the Yamassee war.

After the war they were broken, and were more like a few refugee

families scattered near their former homes. They would linger for a

few decades as separate bands, but after a time they would have to

assimilate, and lose their separate identites, to a large degree.

Only the Catawba would remain un-assimilated, but their numbers too,

would continue to decline.

Map

14. Below we have another map from 'The Catawba Indians' by Brown. It is dated about 1725. It too, is between pages 32 and 33. The map isn't geographically accurate. At the southern end of the map is the city of Charleston. At the Northeastern end is Virginia. The northwestern end has the Cherokee, and beyond them the Chickasaw. Thee is a direct route from both Virginia and Charleston, South carolina to Nasaw, which is cited as being the Catawba. They are at the center of the map, so perhaps the map was made by a Catawba.

Between the Catawba and Virginia

is only one settlement – Saxapaha. It is dated 1725 and seems be

the same location as the Indians said to be on Flatt River, in 1732.

See my previous blog entry. The Succa are between the Saxapaha and

the Catawba. They have to be the Sugaree. The Suteree are far closer

to the Catawba, due east of them. They must be the Shackori. To the

south and much closer to Charleston is Charra. To their north is

Youchine. What is that? Without the 'n' this becomes 'Youchie' – was

there a small Yuchi/Euchee settlement there? Wiapie is next closest to the Catawba. Is this Wiamea?

There are four more communities to

the South and west of the Catawba. There is the easily recognized

Wateree. Then we have the Wasnisa, Casuie, and Nustie. Notice the

'Nisa' ending for Wasnisa. It is similar to Nasaw. Is this the

Waxhaw? The others, I can't figure out. Maybe Congeree or Saponi? We

know a band of the Saponi would move North of the Catawba near

Salisbury in 1729. They were said to have been called Nasaw at times,

too. Without further knowledge, I might never figure them out.

Map 15.

The map below I had earlier missed. There are several maps between pages 32 and 33 in "The Catawba Indians" by Douglass Summers Brown. This is one that I had earlier missed, so I am adding it now, two weeks after I put up this blog post. This map, dated 1733, does show the locations of several bands at this time. It has the Keawee just to the north of the Saraw, who are on the north side of the Pedee River. Downstream from them are the Pedee. The Congaree are still on the map. To their north, in succession, are to the north the Watarees, to their east the Sugaus, to their northwest the Waxaus, then following northwards, the Sataree, and Catapaw. So we see more Catawba communities than we previously had seen, and henc his map needs to be included. Also notice there are still some Yamassee around, in the southeastern portion of the map. Please note the shrinking land base of these Indians.

Map. 16.

The map below is from 'The

Catawba Indians', by Brown, between pages 32-33. It shows several

Eastern Siouan communities and is dated to 1750.The map below I had earlier missed. There are several maps between pages 32 and 33 in "The Catawba Indians" by Douglass Summers Brown. This is one that I had earlier missed, so I am adding it now, two weeks after I put up this blog post. This map, dated 1733, does show the locations of several bands at this time. It has the Keawee just to the north of the Saraw, who are on the north side of the Pedee River. Downstream from them are the Pedee. The Congaree are still on the map. To their north, in succession, are to the north the Watarees, to their east the Sugaus, to their northwest the Waxaus, then following northwards, the Sataree, and Catapaw. So we see more Catawba communities than we previously had seen, and henc his map needs to be included. Also notice there are still some Yamassee around, in the southeastern portion of the map. Please note the shrinking land base of these Indians.

Map. 16.

Starting in the north, we have

'Cuttaboes, or Nasaue Towne' and it says 'The gate to Virginia Road'.

Upstream is 'Sugar Towne', meaning the Sugaree. Just below is

'Wateree Towne'. Just beneath these are 'Wateree, Chicasaw, Sugar

Ditto, and Waxahaw Towne'. There are a couple of places that look

abandoned, Old Wateree Town and something that looks like a fort at

the mouth of Congeree Creek.

Map

17.

In the year 1756, the following

map represents the Catawba Indians. The map is from 'The Indians of

the New World', by James H. Merrell, page 163.

We have Nasaw and Weyapee close

together. To the south is Noostie Town. To the east we have three

more towns. From north to south, they are Charrow Town, Weyane Town

or ye King's Town., and Sucah Town. We have Nustie and Weyapee from

the Deer skin map in the 1725. We are missing Wateree and Waxhaw

towns from the 1750 map, but they are replaced by Weyane. So in only

6 years the map has changed drastically. Also the Chickasaw in their

communities have gone, probably back home to Alabama and Mississippi.

All these things are background material to help understand the Saponi to their north, and what became of them. It is my hope that understanding all this background material will help us understand them, as well, and the Melungeon communities that they spawned.

Why

the Decline?

I have wondered why various bands moved around so much. Why did their

numbers decline so rapidly? After sme study, I think I have found four reasons -- War, slavery, disease, and assimilation. And the English settlers brought about all these things.

Wars of Conquest

The Manahoac,

also recorded as Mahock,

were a small group of Siouan-language

American

Indians in northern

Virginia

at the time of European contact.

The Manahoac,

also recorded as Mahock,

were a small group of Siouan-language

American

Indians in northern

Virginia

at the time of European contact. They numbered approximately 1,000

and lived primarily along the Rappahannock

River west of modern

Fredericksburg

and the fall

line, and east of the

Blue

Ridge Mountains. They

united with the Monacan,

the Occaneechi,

the Saponi

and the Tutelo.

They disappeared from the historical record after 1728.[1]By

the 1669 census, because of raids by enemy Iroquois

tribes from the north and probably infectious

disease from European

contact, the Manahoac were reduced to only fifty bowmen in their

former area. Their surviving people apparently joined their Monacan

allies to the south immediately afterward. John

Lederer recorded the

"Mahock" along the James

River in 1670. In 1671

Lederer passed directly through their former territory and made no

mention of any inhabitants. Around the same time, the Seneca

nation of the Iroquois

began to claim the land as their hunting grounds by right of

conquest, though they did not occupy it. [2][3][4]

- Johnson, M.; Hook, R. (1992), The

Native Tribes of North America,

Compendium Publishing, ISBN 1-872004-03-2,

OCLC 29182373

-

Swanton, John R. (1952), The

Indian Tribes of North America,

Smithsonian Institution, pp. 61–62, ISBN 0-8063-1730-2,

OCLC 52230544

-

Egloff, Keith; Woodward, Deborah (2006), First

People: The Early Indians of Virginia,

University of Virginia Press, p. 59, ISBN 978-0-8139-2548-6,

OCLC 63807988

- Fairfax Harrison, 1924, Landmarks of Old Prince William, p. 25, 33.

The

Xualae were a

Native American people who lived along the banks of the Great

Kanawha River in what is today West

Virginia, and in the westernmost counties of Virginia. The

Cherokee,

expanding from the south, seized these regions from them during the

years 1671 to 1685.[1]

Luther

Addison, 1988, The Story of Wise County,

p. 6.

Eckert,

Allan W., That Dark and Bloody River.

(New York: Bantam Books, 1995) p. Xviii

So

it appears the Six Nations forced the Eastern Siouans to abandon

their lands in Northern Virginia, and the Cherokee forced the Xualla

(also called Joara) to abandon their lands in Western Carolina. In

fact the 'Qualla” boundary, the place where the Eastern Cherokee

live today, was taken from the name “Xualla”, the people who

inhabited those lands before the arrival of the Cherokee.

But

there is another reason for the decline in numbers of the Eastern

Siouan peoples – Slavery.

The

Slave Trade

Here are a few excerpts about capturing Indian

slaves from “The Indian Slave Trade” by Alan Gallay. Every

serious researcher of the indians in the American Southeast should

read this book. I should also warn you that it might make you cry.

One reason there was so much warfare is that slave traders demanded

this trade in slaves as a means for the Indians to pay off their

debts. In a tyial slave raid, the men would be killed, and the women

and children taken to the traders, who in turn sold these women and

children on the slave markets of Charleston.

p. 60. The proprietors

rhetorically asked governor Joseph Morton (September 1682-August

1684; October 1685-November 1686) why the colony had no wars with

Indians when it was first founded and weak and then had warred with

the Westo “while they were in treaty with that government . . .

The proprietors astutely recognized the Carolinians turned them [the

Westo] into enslaving Indians.” Reprehensibly then, the colony

began a war with the Waniah, a group of Indians who lived along the

Winyah River, “under pretense they had cut off a boat of runaways.”

The Savannah [Shawnee] then captured [the] Waniah and sold them to an

Indian trader who shipped them to Antigua. . . . [The proprietors]

learned that the Savanah were at first not going to sell the Waniah

but had been intimidated by slave traders into doing so.

p. 61. The proprietors also received word that the surviving

Westo had wanted peace with Carolina . . . but the messengers were

sent away to be sold. The same fate befell the messengers of the

Waniah. Sarcastically the proprietors rued, “but if there be peace

with the Westohs and Waniahs, where shall the Savanahs get Indians to

sell the Dealers in Indians”? The proprietors were sure that the

cause of both the Westo and Waniah wars, and the reason for their

continuance, lay in the colonists desire to sell Indians into

slavery. . . .

Even some of the Indian dealers wrote privately to the

proprietor of the greed that had led to the enslavement of friendly

Indians. . . . You have repaid their kindness by setting them to do

all these horid wicked things to get slaves to sell to the dealers in

Indians and then call it humanity to buy them and thereby keep them

from being murdered. The proprietors questioned the morality of

attacking all the Waneah for the crimes of a few . . .

p. 62. In 1680, they [the proprietors] limited

enslavemet of Native Americans to those who lived more than 200 miles

from Carolina, though they left the door open to abuse by stipulating

this applied only to Indians in league or friendly to the colony. This law might explain why the Saura moved from the Dan River to the Pedee. It would have been harder for the slave raiding Shawnee and Seneca to get to them. And being nearer Charleston, they were within he 200 mile range spoken of in this law.

p. 210-211. The Catawba was a name the English

used to describe many of the Piedmont Indian groups of both North and

South Carolina (20).. . . .The Catawba, under Carolinian beckoning,

official or otherwise, had prayed on the Savannah (Shawnee) . . . The

Savannah, probably in revenge, then attacked some of the Northward

Indians, a designation the colony used to describe the Catawba and

other Indians of the Piedmont.. They also carried away several of our

Indian slaves away with them (21) (about 1703). Bull appeared in

October 1707 and reported that he had learned from the Shutteree, a

Piedmont group, that 130 Indians calling themselves Savannah and

Senatuees (Santees?) [Vance's note: The author is wrong – has to be

Seneca's. The Santees were allied to the Piedmont Indians whereas the

Seneca were their enemies] fell on them. . . . The force carried

away 45 women and children, but mostly children. A Cheraw Indian

(from a group then in the Piedmont) informed Bull that the attackers

traded with the white men at their own homes and that they lived but

30 days journey from us. Apparently, if this report was correct, the

Savannah were selling their captives in Virginia, Maryland, or

Pennsylvania. . . . (26) as for the Savannah, not all of them would

leave the colony. About a third of the population remained I their

settlements along the Savannah River. (27-28) Those who left would

continue their attacks on the Piedmont Peoples.

p 239. One of the evils he noted in this and

other letters concerned the enslavement of peaceful Indians, which

threatened the harmony of the province. One can almost hear him sigh

with resignation when he recorded: “I hear that our confederate

Indians are now sent to war by our traders to get slaves.” (55)

p. 242-3. The commission of the Indian trade met

first on September 20, 1710 in Charles Town. . . . The commission

undertook a flurry of business, mostly hearing complaints against

traders for illegal enslavement of free Indians . . . The

establishment of the commission opened a floodgate of grievances

against the traders for crimes against the traders for crimes ranging

from assault and battery to kidnapping, rape and the enslavement of

free people.

Heard enough yet? Well I have. Now to the statistics

Gallay brings out. He goes on to say after the Yamasee war, Indian

slavery gradually died out by 1720. I suspect the reason is that

there just were no more easily obtained Indians to enslave. At one

point in the book the traders boast that there are no more Indians in

Florida, as they have all been taken as slaves. When Gallay speaks of

Piedmont or low country Indians, he is talking of the Eastern Siouan

peoples, the Catawba and members of the Catawba Confederation. He

continues;

p. 298-299. There is no

telling how many Piedmont and low country Indians . . . were enslaved

. . . and there is evidence all members of these groups were

enslaved, but there are no numbers . . . The Lord Propritors

frequently complained of illegal enslavement . . . all told, 30,000

to 50,000 is the likely range of Amerindians captured directly by the

British, or by Native Americans for sale to the British., and

enslaved before 1715.

Gallay

says the numbers enslaved ranged from a low range of 24,000 to

32,000, to a high range of 51,000. He also ads that excluding the

Creek, Cherokee, Savannah, and Piedmont Indians, 25,000 to 40,000

were enslaved. Doing the math, knowing there were few Creek and

Cherokee enslaved, we have a low range of between 5,000-7,000, to an

upper range of 10,000-11,000 of these Piedmont Indians were enslaved, from the

period of 1670-1715. Various Indian tribes went to war to capture

enemy Indians, and sell them to the English, who in turn exported

them to the Caribbean, exchanging them for African slaves. American

Indians would just run away the first chance they got, living off the

land until they arrived back home. But the Africans were afraid to

run away, not knowing the landscape very well, and being afraid of

the American Indians they might run across.

He continues on

page 299, to say “What is

surprising about these figures is that Carolina exported more slaves

than it imported before 1715.”

Disease

p 90. The Catawba Indians, by Douglas Sommers

Brown; The Congarees were a “comely sort of Indian”, who had

already been much reduced in numbers by small-pox.

Date is about 1718.

p 154 The Catawbas however, were greatly

dissatisfied with the Charles Town traffic,

(May 1718),. . . but most of all, the

Catawbas were tired of serving as burdeners, the cause of their

losing so many men” Brown

says, quoting Wiggan, “the

burdeners were quickly sent back to the Nation because of their

getting the small pox in our settlements.”

p 180; The Catawba Nation had interittenly been

attacked by an enemy even more formidable than either the white

settlers or their northern enemies. The other assailant was small

pox. Brown

goes on to say it had appeared as early as 1697.Lawson says the

disease had been among the Catawba shortly before his visit. In 1738

spallpox spread throughout Catawba country, according to Adair.

p. 181. The South

Carolina Gazette in 1759 reported that it is pretty ecrtain that the

small pox has lately raged with great violenceamong the Catawba

Indians,, and that it has carried off near one half of that nation. .

. The Warriors returned from Fort Duquense had brought small pox back

with them.

Per Brown (same

page) Maurice Moore wrote, “Their

numbers were reduced to less than one half . . . by the small pox.

The tradition that I heard in my boyhood was that it was introduced

through the avarice of some of the White men. There

is a citation and a note saying “It

is not inconcieveable that such an atrocity was perpetrated. When

Jeffrey Amherst, England's commander in chief in North America, heard

of the outbreak of Pontiac's War, he instructed Col. Henry Bouquet,

saying, I wish to hear of no prisoners . . . could it not be

contrived to send the small pox among these disaffected tribes of

Indians?” (see

Van Every, “Forth to the Wilderness”, p. 10).

Assimilation

There is only one band of the Eastern Siouan tribes that is federally

recognized – the Catawba. Some Tutelo descendants are part of the

Six Nations. It is known that some federally recognized tribes

adopted known Catawba (Creek, Cherokee and Choctaw). The Lumbee have

been fighting for recognition for 150 years, longer than probably any

other tribe. There are several state recognized bands – Occoneechi

Band of the Saponi, the Sapony, Haliwa, Monacan, Waccamaw. The

Melungeons can prove a Saponi heritage, but to my knowledge, have

never considered trying for federal recognition. But for the most

part, the federal government has decided that these descendants have

already been totally assimilated into American Culture, have a

minimal amount of American Indian blood and DNA, and therefore do not

deserve the right to be considered American Indian, with the status

that goes along with it.

Conclusion

The

Eastern Siouans, at the time of first contact with Europeans, were a

strong people, from West Virginia in the north, through the Southern

Appalachians, Virginia and the Carolinas to the Atlantic coast of

South Carolina. Through periodic small pox epidemics, constant

warfare, the slave trade and finally assimilation through cultural

contact and intermarriage, the culture has virtually died. Were it not for the English settlers, none of these things would have happened. Granted, they were perpetually at war with their neighbors, but it was not a war to extinction. The English traders demanded war, and they demanded the capture of slaves to settle their debts to the traders. This caused both the Tuscarora and the Yamassee Wars, that spelled the end of several Eastern Siouan Bands. Only a few Indians remained, scattered wherever they could live.

These

things are a prerequisite to understanding mixed race peoples, such

as the Melungeons, or others similar to them.

Thank you so much for this post! So much valuable information gathered into one place.

ReplyDelete