CHAPTER III, WAR

As with the last chapter, the maps are off and the citations are, too -- will have to finish both later.

Per

Blumer, the Tuscarora Wars has several causes. He says I.] The

Indians objected to the settlement of New Bern, North Carolina in

1710. ii.] The Indian traders also cheated the Tuscarora Indians

regularly. The last straw was iii.] The ill treatment of intoxicated

Tuscarora by a settler. This caused a major confrontation with North

Carolina. Also Seneca agitation pushed the Tuscarora towards a major

confrontation with North Carolina. Remember many of these Indian

Traders were the scum of the earth. They would make it mpossible for

the Indians to pay them back, then at the last minute tell them if

they capture enemy Indians for use in the lsave trade, their debt

would be forgiven. This happened once too many times to the

tuscarora, an they got to the point where they couldn't take it

anymore, and they picked up the hatchet against the English.

The

Tuscarora attack was carefully planned. At dawn, September 22nd,

1711, over 130 settlers were killed by noon. Survivors fled to Bath

and New Bern. For the next four months, the Tuscarora pillaged at

will. Captives were regularly tortured, and eventually executed.

North

Carolina was a small, weak colony at the time. South Carolina finally

had the excuse they'd waited for a long time, and siezed the moment

to attack the Tuscarora. They hoped to become rich selling off the

Tuscarora into slavery. South Carolinian Captain John Barnwell left

Charles Town with only 30 men, but travelled inland to recruit

Piedmont Indians and then pounce on the Tuscarora from the west.

Blumer says that it is thought the Tuscarora had only recently moved

south into North Carolina, onto Catawban lands. I do not know the

evidence for this. But we do know the Tuscarora and the Catawba were

traditional enemies, and this had been the case for some time. They

needed no convincing to go to war with the Tuscarora. The Yamassee

were also recruited. The Tuscarora were no match for their combined

forces. Blumer says Barnwell recruited 500 Indians, 350 of which were

Catawba and their allies. Blumer mentioned Congaree, Waxhaw, Wateree,

Cheraw and others allied to these Catawban peoples. The rest were

Yamasee. Thornton believes the Yamasee were of Muscogeean origin,

saying the term “yama” implied they had been traders themselves.

Blumer

gives an impressive view of what a Catawba warrior looked like in the

old days. I feel I need to report what he says of their appearance.

He says:

He says:

“The

Catawba and their allies went to war in the traditional way. The

women combed their men's hair with bear grease and red root. The

men's ears were decked out with feathers, copper, wampum, and even

entire birds wings. The men painted their faces with vermillion.

Often one eye was circled in black paint, and the other in white.”

War

dances were performed, and the men set out looking as fierce as

possible.

Blucher

goes on to say some had guns and others had bows and arrows. He says;

“In

full traditional battle attire, the Catawba must have been an

impressive site. The name of the Catawba War Captain who led the

nation on this expedition has been lost to history. None of the

Indians would enter a war party without the urging of a powerful war

captain who had won the right to carry snake images on his person in

paint or tattoo.”

Earlier

we saw that the snake image was associated with the Occoneechi.

However there is no mention of the Occoneechi as being a part of this

war party, so maybe something else is in play. Now Indian warfare was

not as Barnwell had expected. The first battle was at the Tuscarora

village of Narhantes. The Catawba took as many captives as they could

get their hands on, and headed for the slave markets of Charleston to

sell them. The Catawban peoples seem to have expected this as just

another slave raid. It makes me wonder if they'd been on other slave

raids. They seemed to know exactly where the slave markets were. By

the end of February 1712, Barnwell's army consisted of about 90

Whites, and 148 Indians, mostly Yamassees. On March 1st,

Barnwell's army entered Tuscarora King Hancock's town, which was

deserted. On March 5th,

King Hancock's fort was surrounded. He threatened to torture his

captives in frout of Barnwell's men. Both sides agreed to hold a

conference on March 19th

at

Bachelor's Creek. The Tuscarora did not show up.

Barnwell's

reputation began to slide. He was forced to return to the Catawba

towns, and get them to return to the battle. On April 7th,

Barnwell's reinforced army returned to Hancock's Fort. These attacks

lasted 10 days. Again, his Catawba allies gathered as many captives

as possible, and headed to the slave markets of Charleston.

Blumer

adds;

“Disappointed

but determined to turn a profit, Barnwell on the pretext of a

meeting, met with the Indians Near Bern. Once inside the fort, these

unfortunate souls were held captive and shipped off to Charleston.

Barnwell would have his profit in Indian flesh.”

As

a result of Barnwell's short but bloody Tuscarora incursions, all the

Indians lost their confidence in the Christian Whites. The Tuscarora

began their exodus to Canada, to be with their Iroquoian relatives.

The Five Nations were destined to become Six, with the addition of

the Tuscarora. They ever afterwards held a grudge against the Catawba

and their allies. Because of Barnswell's actions in obtaining his

own slaves, the Catawba quit trusting the Whites. These events would

lead us to the next war with the Tuscarora.

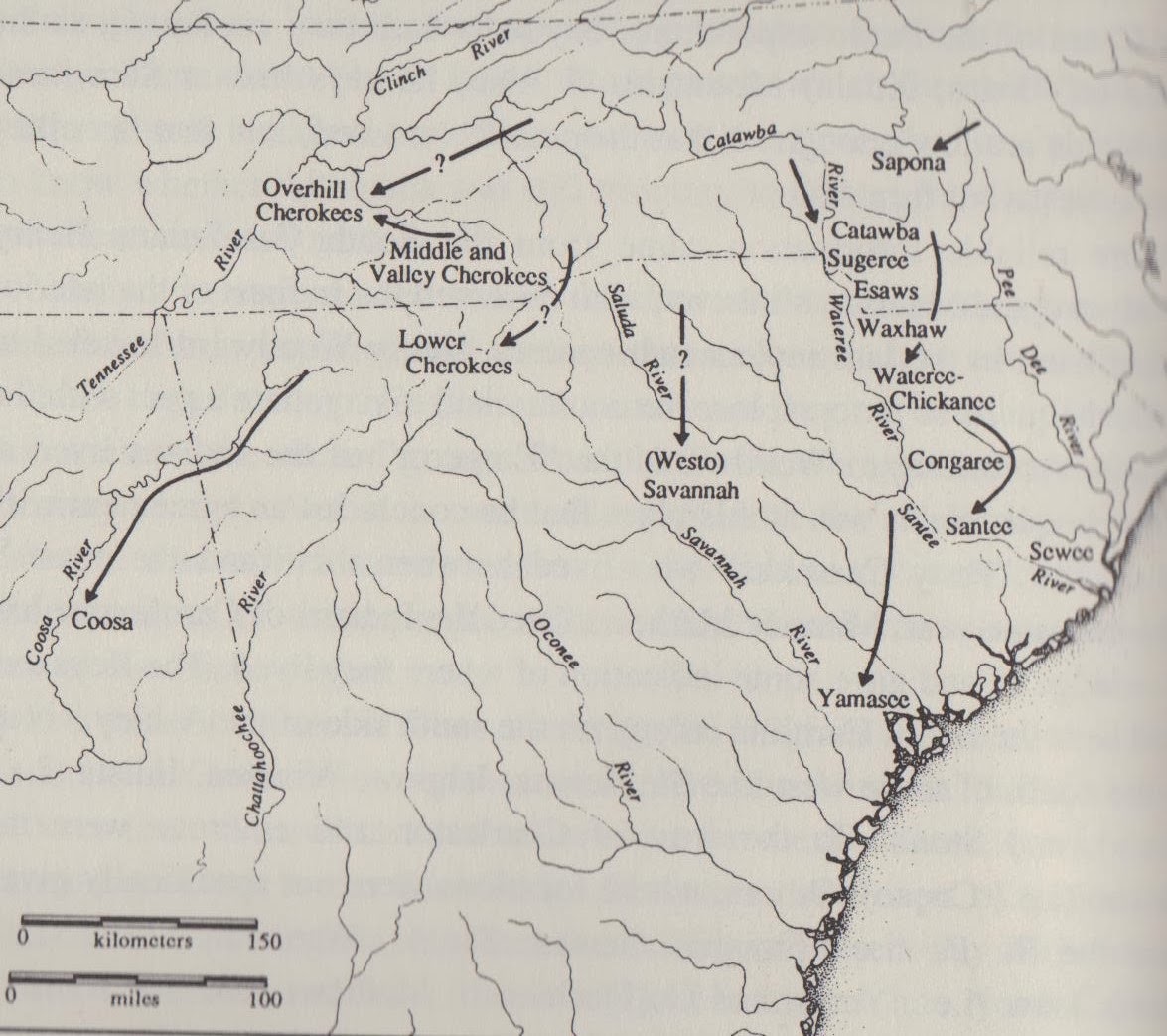

On

the next page

is a map of the route the John Barnwell's troops took on their was to

attack the Tuscarora. The map was from page 36 of Catawba Nation,

Treasures in History, by Thomas J. Blumer. The Tuscarora War lasted

from 1711-1713 and ended in the utter destruction of the Tuscarora

and Coree Indians.

Map 9. The First Tuscarora War

There

is another important Band of the Yesah Nation – the Saura. The

Spaniards found them living in Western North Carolina, and called

them the Xualla (De Soto), or Joara (Pardo). Map 7 has the Saura on

the upper Dan River by 1700. They were said to have left the Upper

Dan in 1703. By the time of the Tuscarora Wars of 1711-1713, they are

on the Pee Dee River (map 8) South and East of the main Catawba

towns, and they took part in the first, but not the second Tuscarora

War (map 9). Map 12 still has the Cheraw on the Pee Dee River in

1720. Many researchers say that the modern Lumbee Indians are

remnants of the Old Cheraw. Map 14 shows the actual locations of

Upper and Lower Saura Towns on the Dan River before they were

abandoned about 1703. About this time frame many Eastern Siouan

cities in the western parts of Carolina and northern Virginia were

abandoned as they removed themselves eastwards and southwards.

On

the deer skin map (map 15) dated 1725 the Charra are one the bands

living near the Catawba. On the 1756 map (map 17) there it is,

Charrow Town next to the Catawba. There is no Charrow Town on map 16,

dated about 1750. They seem to have maintained an existence longer

than many other bands. As I said, many speculate that the modern

Lumbee Indians of Robison County, North Carolina are some of their

descendants.

The

Second Tuscarora War

As

Blumer states, The Tuscarora continued to ravage the countryside,

just before their exodus to the north, in the same way the Israelites

spoiled the Egyptians before fleeing Egypt. Settlers remained behind

palisades and fortresses, afraid to venture out, but doing little to

help themselves, depending mostly of South Carolinians. Some fled the

colony. In June 1712, a delegation of North Carolinians again asked

South Carolina to come to their rescue.

Colonel

James Moore set off from Charleston in October, 1712, to gather an

Indian army. Per Gallay, Moore had led many expeditions to gather

Indian slaves. He led the 1704 raid into Florida to enslave most of

the Apalache Indians. Gallay records that Moore's Indian allies were

Creek. They attacked and wiped out several Appalache towns, taking

hundreds of slaves. He says four Appalache towns moved to South

Carolina which promised to protect them. (x)

Blumer

then says something of note. He says; After

Barnwell's deception, Moore's recruiting was rather slow. Rather than

halt at Waxhaw Town

(as

did Barnwell), he

marched further to the Catawba towns, presumably to coax the Catawba

directly. His first task was to convince the Catawba War captians

that a war against the Tuscarora was to their advantage . . .once the

war captains agreed, they began the war ritual. He took up a pot drum

and danced counterclockwise around his house, performing a call to

war song. When a crowd of men gathered, the war captian recited the

crimes of the Tuscarora against the Catawba. Then the war captain and

their men fasted for three days. They purged their bodies of

impurities with the powerful emetic button snakeroot.

Colonel

Moore crossed the Cape Fear River with 500 Catawba and their Catawban

allies, 300 Cherokee and 50 Yamassee; 33 Whites led the force. They

joined 140 members of the North Carolina militia. [32.]

Meanwhile,

not all the Tuscarora were part of the rebellion. King Blount

delivered King Hancock, leader of the rebellion, to the North

Carolinians, who was then executed. Moore, rather than attack the

Tuscarora, stayed in the North Carolina communities of New Bern, and

Bath, and Albemerle. Without provisions, the Indian army gathered

provisions amongst the settlers, eating their cattle and other

rations. While Moore waited, the Tuscarora strengthened their

fortress at Neoheroka. Their fortress consisted of 1.5 acres of man

made caves, palisaded walls, and strong buildings with a source of

water inside. After a bloody battle, Fort Neoheroka fell on March

20th,

1713. 475 Tuscarora were killed and another 415 were sold into

slavery. This was the end of the Tuscarora resistance. A band of the

Tuscarora remained in North Carolina with King Blount, and others not

sold into slavery. Most however fled north to join their Tuscaroran

relatives who had already fled to live with the Six Nations. [33.]

Blount's band of Tuscarora fled to Virginia at the invitation of

Governor Spotswood where they became close neighbours with the Saponi

who were living next door to them at Fort Christanna.

From

this time forth the Six Nations and the Catawba would be at war until

the power of the Catawba and their allies were completely and utterly

shattered.

Also

notice the mention of how Moore went beyond the Waxhaw. Later a claim

is made that the Catawba destroyed the Waxhaw, but that claim was

made by the South Carolinians. We know it was said there were only 50

Yamassee with Moore, whereas there were hundreds earlier. We also

know Barnwell took friendly Indians as slaves to the slave market in

Charleston. It might be argued that the Waxhaw village and some of

the Yamassee were those so enslaved.

We

shall also see the small pox killed off many of the Indians,

including the Catawba. The Catawban Indians and their confederated

bands proved unable to battle all these foes at one time. Eventually

their numbers were to dwindle to a pitiful few that would forgot much

of their heritage. I hope to write these things to re-asemble a coal

of a fire, to share a lamp of light in the darkness of the history of

the people. There was still one more great war for the Catawba to

fight on their own behalf. At the end of the Yamassee War, the way of

the Carolinas would change forever.

Map 10. The Second Tuscarora War

The

map above shows the routes taken by the warriors and soldiers during

the destruction of the Tuscarora in the second Tuscarora War.

Map

11. The Movements of Some Catawban Bands About 1715

The map below shows the locations of the Southern Bands of the Carolina

Siouans about the year 1715. This would be just after the massacre of

the Tuscarora and Coree Indians, yet just before the Yamassee War, a

war during which many Siouan bands would disappear, or or be so

reduced in number they would be soon forgotten. It is taken from page

186 of 'The Juan Pardo Expedition', Charles Hudson.

The

Northern Bands all were under the banner of the Saponi and near Fort

Christanna. The Central Bands were all East of the Catawba and the

bands associated with them, very close to where the Catawba are today

Those East of the Catawba were mostly in central North Carolina.

There were also the Settlement Indians who lived in and around

Charles Town. Some of these were Creek, some former Spanish allies

from tribes wiped out in the slave raids of Moore and others, and

some most certainly would have been Catawban. Some might have been

freed or runaway Indian slaves whose tribes or bands no longer

existed. Tribal identies were getting blurred as remnants of the

Yamassee, Notchie (found all over the Southeast after their Nation

was destroyed by the French along the Mississippi River), Appalache,

Westo, Chowan (Shawnee), and other wasted tribes would form new

communities huddled together for protection.

Map 12. The Distribution of Indian Tribes about

1715

The

map above is also about the same timeframe, about 1715. Notice the

Cherokees are near where the Coosa Indians (Creek) had been 100 years

earlier, according to Spanish records. The Cherokees are pushing the

Creeks further to the South. The lands of the Siouans are also

shrinking and they aren't realizing it, it seems. They have lost most

of their lands in Virginia and South Carolina as well, to the White

settlers. It was taken from 'The Catawba Indians, The People of the

River', by Douglas Summers Brown, between pages 32 and 33.

The Yamassee War 1715-1717

Although

the next conflict of the era is called “The Yamassee War” of

1715-1716, the Catawba were the largest Indian component with 570

warriors – Blumer tells us that King

Whitmannetaugehehee was king during the time of the Yamassee War. So he must have been the war leader who led his people during those hard times.

I

have found nothing telling which Indians that Moore and Barnwell took

as slaves, other than some of them were the Tuscarora and their

allies, the Core, but they may have taken some of the Piedmont

Indians. It is interesting to note that at one time the Eno were

called allies of the Tuscarora as were the Saxipahaw. Perhaps Barnell

or Moore rounded them up as slaves, and used the excuse that they

were allied to the Tuscarora. That would explain the alliance between

the Yamasee and the Catawban peoples in the next war. They just got

tired of the English betraying them.

The

Yamassee by comparrison, supplied only 400 warriors. According to

Blumer, “All

the Catawban speaking groups in both of the Carolinas joined this

effort to expel the Europeans from the Southeast.”

Per

Blumer; The

Indians had many grievances against the settlers. They included

abuses of a cruel and obscene nature committed by the white traders

who worked among the Indians. i.] Abuses such as murder and rape were

common. ii.] If needed, they would help themselves to the Indians

crops and not pay for the food.. iii.] In addition, the traders

fomented Indian wars to foster the Indian slave trade. iv.] Other

grievances included white settlements that encroached on Indian

lands.

Blumer

says the war was instigated by the Creek Indians, but the settlers

thought it must have been instigated by the French at Mobile Bay, or

the Spaniards at Saint Augustine. Blumer also speaks of the sale of

free Indians into slavery by unscrupulous traders in the Indian

towns. These are many of the causes and sentiments for the origins of

the Yamassee War

of 1715-1716. Virtually every Indian community took part in this

rebellion.

On

April 15th,

1715, ninety percent of the traders working in the Indian towns were

killed. In the process, 40 colonists were killed. South Carolina

mustered an army under General George Chicken. Per Blumer, The

Indians suffered a defeat at Goose Creek, and the Catawba and their

allies had second thoughts about the war. On July 19th

,

1715, the Catawba sued for peace. . . on October 18th,

1715, a delegation [of

Catawba] went

to Williamsburg, Virginia. A

second conference was called on Feburary 4th,

1716. Virginia Governor Spotswood wanted the Catawba headmen to

deliver their sons of their headmen to Fort Christanna. This exchange

occurred by April of 1717. The end of the war occurred when the last

of the Yamassee fled to Fort Augustine, Florida. Those not lucky

enough to flee were sold into slavery. It is thought some of the

Yamassee took shelter with the Catawba, and some with the Creek. But

their tribe is now considered extinct as a nation. An English record

states “Yamassee

speak the same language as the Lower Cherokee . . .”

(1AL1). This record is dated January 24-25,1726. So it is possible

that some Yamassee took refuge with the Lower Cherokee as well. At least

two Yamassee towns, Tomatley and Tuskegee, vanish and are later found

in the Cherokee Nation, and are considered Cherokee towns.

The

Yamasee War

http://scholarcommons.sc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgiarticle=1023&context=archmonth_post

Here

is a second account of the war. Chester B. DePratter Ph.D.; South

Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology University of

South Carolina The Yamasee War Jon Bernard Marcoux Noreen Stonor

Drexel Cultural and Historic Preservation Program Salve Regina

University

On

Good Friday, April 15, 1715, the chaos of war invaded the lives of

the European colonists, enslaved Africans, and Native Americans

living in South Carolina. The Yamasee War began that day when a

number of trade officials were murdered in the Yamasee town of

Pocotaligo. The murders took South Carolinians completely by

surprise, as the Yamasee were thought to be one of the colony's

closest Indian allies. Indeed, the murdered Englishmen had only been

sent to Pocotaligo in order to arrange talks with another Indian

group, the Ochese Muskogeans (later Creeks), who were rumored to be

planning attacks against South Carolina traders and settlers. These

initial murders were quickly followed by major Yamasee attacks on

plantations around Port Royal, near modern day Beaufort, SC. In these

attacks, the Yamasee managed to kill over 100 colonists and set the

rest of the settlement's population to flight. In the following

weeks, news began to filter into Charleston that the English traders

in virtually every southeastern Indian village had either been killed

or chased off. Adding to the fears of a pan-Indian assault, news

emerged that the Catawba and a small group of Cherokee had made raids

on plantations north of Charleston and even managed to capture a

South Carolina militia garrison. Facing this apparent “invasion,”

colonists across South Carolina fled to Charleston, where the effects

of overcrowding, fear, and tension, exacerbated by the summer heat,

took its toll on the physical and mental health of many residents

(Crane 2004; Oatis 2004)

Historians

and archaeologists have been studying this conflict for over two

centuries, yet most of the public is only vaguely aware of the

Yamasee War or its significance outside of South Carolina. Indeed,

historian William Ramsey (2008) states that the Yamasee War

(1715-1717) “easily ranks with King Philip’s War and Pontiac’s

Rebellion” as a key colonial conflict; however, compared to these

other wars, it remains woefully understudied. As we recognize the

300-year anniversary of the conflict, there has been an upsurge in

scholarly interest in the Yamasee War. The results of these new

projects will doubtless provide new insights for understanding this

pivotal moment of the colonial period.

The

Yamassee War included a small number of what might be called major

military engagements, and these were confined to the first three

months of the war. Afterward, hostilities were limited to Yamasee and

Muskogean raids on trading caravans and frontier skirmishes with

South Carolina militia that continued sporadically for the next two

years. Peace with the last of the hostile groups, the Lower Creeks,

officially ended the war in 1717. While rare, the major battles

described below were nevertheless significant, for they included

hundreds of combatants on each side and were fought on two separate

fronts (north and south of Charleston). Furthermore, these battles

were like microcosms of the colonial landscape, defining

relationships among the period’s three major cultural groups –

Europeans, Native Americans, and enslaved Africans. Indeed,

historical accounts of these battles are clear that almost half of

Carolina militia forces was comprised of enslaved Africans.

Pocotaligo and Yamasee Raids on Port Royal: April 15, 1715 At

daybreak on this day, a colonial delegation from Charleston was

brutally tortured and murdered by Yamasees at the town of Pocotaligo

near modern-day Beaufort, SC. The scene is described in chilling

detail by Charles Rodd, a Charleston merchant. In a 1715 letter to

his employers in London (Rodd 1928). Describing the attack and

torture of Indian agent Thomas Nairne writes, “But next morning at

dawn their terrible war-whoop was heard and a great multitude was

seen whose faces and several other parts of their bodies were painted

with red and black streaks, resembling devils come out of Hell…

They threw themselves first upon the Agents and on Mr. Wright, seized

their houses and effects, fired on everybody without distinction, and

put to death, with torture, in the most cruel manner in the world,

those who escaped the fire of their weapons… I do not know if Mr.

Wright was burnt piece-meal, or not: but it is said that the

criminals loaded Mr. Nairne with a great number of pieces of wood, to

which they set fire, and burnt him in this manner so that he suffered

horrible torture, during several days, before he was allowed to die.”

Rodd goes on to describe the harrowing escape of families from their

plantations around nearby Port Royal as the Yamasees began their war.

You

might wonder about poor Mr. Nairne. He seems to have been

deliberately chosen to be tortured. Perhaps he was. He was one of the

biggest dealers in Indian slaves around. Such

slave raiding took place on a great scale. In 1715 trader Thomas

Nairne boasted that the Yamassee Indians had raided the Florida Keys

for slaves as Indians further north in Florida had for all intents

and purposes, vanished, due to all the slave raids. The Indians

finally grew tired of the South Carolina traders, and this resulted

in the Yamassee War of 1715-1717. Hudson says this war was an end to

the Santee, Sewee, Pedee, Congaree, Cusabo and Waxhaw Bands. We hear of the Pedee later, but of the others, we hear very little after this time.

The

“Sadkeche Fight” and Carolina Counter Offensive against Yamasee

Towns: late April, 1715

South

Carolina's military response to the Yamasee raids was swift. Only a

week after the murders

at Pocotaligo, Governor Craven of South Carolina personally led

militia forces against the Yamasees in their own towns. He sent some

of his forces to attack Pocotaligo by water, while he mustered some

250 men to attack overland. Part of this offensive is a battle now

called “The Sadkeche Fight.” In this engagement, Craven was

ambushed in camp while on his march to Pocotaligo somewhere on the

Combahee River near Salkehatchie, SC. A weekly broadside called The

Boston Newsletter, reported on the battle stating, “The Governor

marched within Sixteen miles of [Pocotaligo], and encamped at night

in a large Savanna or Plain, by a Wood-side, and was early next

morning by break of day saluted with a volley of shot from about Five

hundred of the enemy; that lay ambuscaded in the Woods, who

notwithstanding of the surprise, soon put his men in order, and

engaged them so gallantly three quarters of an hour, that he soon

routed the enemy; killed and wounded several of them; among whom some

of their chief Commanders fell” (June 6, 1715). Meanwhile, the

Carolina militia forces sent by water scored decisive victories

against the Yamasee towns near Beaufort, forcing those groups to

retreat southward across the Altamaha River in present-day Georgia.

Santee Raids and Captain Chicken’s Charge: mid May-early June 1715

to Carolina settlers, the scale and violence of the Yamasee attacks

on Port Royal must have been frightening. These fears, however, must

have quickly multiplied when news emerged that a second group of

raids was taking place at plantations along the Santee River north of

Charleston. The fact that these raids were conducted by the Catawba

and Cherokee stoked rumors that these violent assaults were part of a

pan-Indian revolt aimed at driving Europeans from the region. The

first attack occurred at the plantation of John Herne (Hyrne), near

present day Vance, SC. In his 1715 journal, Goose Creek missionary

Francis LeJau says the Indians “killed poor Herne treacherously,

after he had given them some Victuals [food], according to our usual

friendly manner.” Following this attack, the Indians ambushed a

group of Carolina militia sent to the area to investigate.

Twenty-seven of the militia were killed in this engagement. The

invading force then moved on to a fortified plantation known as

Schenkingh’s Cowpen – a site now submerged under Lake Marion near

Eadytown, SC. Here the group was able to trick the commanding militia

officer to let them inside the palisade under the pretense of

surrender. Once inside the defenses, the group pulled out their

weapons, slayed 22 militiamen, and burnt the garrison. It appears

that the raiding Indian force then began to move toward Goose Creek,

which had largely been deserted. The culmination of engagements on

the northern front happened on June 13, when militia captain George

Chicken led a force out to meet the advancing Indian group. A letter

from Charleston merchant Samuel Eveleigh (1715) gives great detail of

the battle stating, “Capt. Chicken march'd from the Ponds [near

Summerville, SC] with 120 men and understanding that they were got to

a Plantation about 4 miles distant marched thither, divided his men

into three parties, two of which he ordered to march in part to

surround them, and in part to prevent their flight into an adjacent

swamp but before the said party could arrive to the post designed

them, two Indians belonging to the enemy scouting down to the place

where Captain Chicken lay in ambascade [sic] he was obliged for fear

of discovery to shoot them down, and immediately fell upon the body,

routed them and as is supposed killed about 40 besides their wounded

they carried away.” This significant engagement, sometimes known as

“The Battle of the Ponds,” halted the advance of the Piedmont

Indians and marked their withdrawal from the war (they sent a peace

delegation to Virginia about a month later). This battle thus

effectively ended the war on the Northern front.

Apalachee

Raid on New London (Willtown) and the Burning of St. Paul’s Parish:

mid July 1715

A

few weeks after Captain Chicken’s victory, Governor Craven marched

with a militia force of about 200 settlers, enslaved Africans, and

allied Indians in order to launch an offensive against the Piedmont

Indians who attacked the northern plantations. Shortly after crossing

the Santee River, Craven received word that a large force of 500-700

Apalachee and allied groups had crossed over the Edisto River and

attacked the colonial settlement called New London, located on

present-day Willtown Bluff, SC. The garrison at New London prevented

the force from entering the town, so the raiding force set about

attacking plantations across St. Paul’s Parish all the way to the

Stono River. The Indians managed to retreat across the Edisto River

and destroy the bridge before Craven’s militia forces arrived. Once

again, Samuel Eveleigh (1715) describes the action, “…the

Apalatchee and other Southern Indians came down on New London, and

destroy'd all the Plantations on the way, besides my Lady Blakes,

Falls, Col. Evans and several others, have also burnt Mr. Boon's

plantations and the ship he was building. The crops thank God are

still pretty good; the Govr. At that instant had

marched the Army to Zantee [sic], however he returned back on the

first notice upon his approach the Indians fled over Ponpon Bridge

and burnt it having killed 4 or 5 white men. We have not since heard

from them.” This incursion marked the last major engagement of the

Yamassee War. In August, much needed military supplies arrived in

Charleston from Virginia and New England. Also, the colonial assembly

passed an act that funded a 1200 man militia and the construction of

ten substantial forts across the frontier. By August, the Yamassee had

also began their withdrawal south to Spanish territory around the St.

Augustine.

There

seem to have been two forces working together that caused this war.

The first being that the Indians saw, day after day and year after

year, settlers encroaching on their land, eating their deer and wild turkey, leaving little food for themselves. A second reason for the

war was the evil of slavery. Traders demanded the people to gather

slaves of their neighbors, to pay their bills. They simply got tired

of doing this.

The

Aftermath of the War

As

for the instigators of the war, only weeks after their first

successful raids, the Yamasee had lost a quarter of their number to

death or slavery, and they were forced to move their towns south to

seek protection from the Spanish. While not creating as perilous a

situation as that experienced by the Yamasee, the chaos of war caused

a temporary but crucial breach in the fundamental diplomatic and

trading relationships among all southeastern Indian groups and South

Carolina. In doing so, the war created a moment when everything was

“on the table” and negotiable. Consequently, the twenty-five year

period following the war (ca. 1715-1740) included significant changes

in diplomacy and trade that reflected the attempts of all groups to

adjust to this new post-war landscape.

In

rebuilding diplomatic relations with Indian groups after the Yamasee

War, South Carolina officials sought to avoid another disaster by

making diplomatic relations with Indian groups as streamlined as

possible. In order to do this, the government attempted to reduce the

number of Indian entities with whom the colony negotiated by lumping

politically independent Indian towns into composite groups called

“nations” and assigning a single individual to speak for the

entire group (Oatis 2004). It was likely the convergence of South

Carolina's nationalizing strategy with the Indians' natural

consolidation due to population loss that resulted in the emergence

of geographically bounded ethnic collectivities we now refer to as

“Creek,” “Cherokee,” and “Catawba” (Knight 1994; Marcoux

2010; Merrell 1989). After this

date you hear less and less about the Cheraw, the Santee, the

Wateree, etcetera, and more and more about them as a whole, as the

Catawba, or the Catawba and their Confeterated/Associarted Bands.

Map 13.

Distribution of the Catawban Bands After the Wars

From

'The Indians New World', by James H. Merrell, page 86, we have the

map above. The historic time when the map was accurate is about 1720.

You will notice several bands no longer exist, or have incorporated

with other bands. This is an indication that they are banding

together for strength, as their numbers have drastically fallen. I

strongly suspect this is due to the Small Pox, and constant warfare

driven by the slave trade. Where the Yamassee once were are now 'the

Settlement Indians'. From the Catawba peoples on the Catawba River to

the Atlantic coast and the Waccamaws, are several small bands of

Eastern Siouan peoples. Notice the Sewees, Santee, Cores and Yamassee

and others have disappeared and the Tuscarora are much smaller. The

Saponi are just west of the remnant of the Tuscarora. Clearly the

Tuscarora and Yamassee Wars have taken a heavy toll on the local

Indian populations. A vast area where the Tuscarora had once lived is

now vacant of people, and thus is opened up for White settlement.

Most of the eastern Siouans had abandoned central and western

Virginia, and this region as well, was opened up for White

settlement. White settlers poured overland leaving the Indians as small pockets surrounded by Whites.

Notice the Saponi have moved to the

northeast and the Cheraw have moved to the southeast. Vast areas of

North Carolina are vacant of Indians, where the Tuscarora and several

bands associated with the Catawba not moving at all. The Esaw, Waxsaw, Santee, Congaree, Eno, Saxapahaw, and others apparently have vanished simultaneously. We have the Saponi (really a

unity of several bands that have moved together for protection) in

the north at Fort Christanna. They represent all the bands previously

in Virginia. It is thought warfare with the Six Nations vanquished

them, but I suspect many were taken in slave raiding ventures by

traders using Indian allies of non-Siouan origins to capture them.

Their absence clears the way of European settlement of central and

Western Virginia by 1700. In or near the coasts of South Carolina we

have the Cape Fear Indians to the north and the Settlement Indians

nearer Charleston, their original band names having been lost to

time. Only the Waccamaw are mentioned by name. Inland a ways are the

Pedees, Cheraw, and Keyauwees. Still further inland we have the

Catawba, Sugaree and Wateree. The Catawba are a grouping of several

bands as well. There are great areas now uninhabited whereas

previously there were several bands of Indians associated with the

Catawba or Tuscarrora. Some of he Yamasee fled to Florida, perhaps to

reamerge generations later to be known as the as the Seminole. The

Tuscarora and Yamassee Wars have left a great deal of both Carolinas

and Virginia uninhabited. With the Indians now all or mostly gone, now these lands are free and open to European colonization.

Hudson contrasts the South Carolina

traders with the Virginia traders. “Unlike

the Virginia traders, the Charleston traders conducted a lively

business in Indian slaves. This becomes so prevalent that in

contemporary documents the statement that the Indians had gone to war

is virtually synonymous with saying they had gone to capture slaves.

. . . Sometimes the traders would force their own Indian slaves to go

out and capture their Indians for slaves as a means of purchasing

their own freedom.”Often the traders would

sell rum (illegally) to the Indians, and get them into a debt that

they could not repay. The traders would then say they would forgive

the debt if the Indians would go to war against a neighboring tribe

to gain slaves of them. [34.] The survivors fled to either the

remaining Spanish Indians near Spanish towns or the Catawba. After

this war, the Catawba and Associated Bands never again acted on their

own behalf in the political realm on account of their being an independent

Indian Nation. All their future actions were were determined by their

being a satellite of the South Carolinian Colony. By the 1730s, the

South Carolinians were far more worried about a Negro slave

insurrection than an Indian revolt. Another account mentions that

until about 1717, the colony exported more slaves than it imported.

In short, there were few Indians left to enslave.

In 1735, John Thompson is called a

trader with the Cheraw Indians on the East bank of the Pedee River.

Hudson names 3 other 'later' traders with the Cheraw – Samuel

Armstrong, Christopher Gadsden, and John Crawford. Hudson says Samuel

Wyley was the most important trader to the Wateree about 1751. He

later became an unofficial agent for the Catawba. Other interesting

traders throughout the 1730's and 1740's were George Haig, and it is

possible King Haigler was named after him. Thomas Brown set up his

trading business at the Congarees about 1730. He had a son named

Thomas Brown who was half-Catawba. In 1748 Haig and Thomas Brown Jr

were captured by the Iroquois. Haig was killed and the young Brown

was freed after being ransomed. A small pox epidemic in 1738

devastated the Catawba. Robert Steil also became a trader at the

Congarees. [35.]

Please notice that Hudson has not

mentioned the Northern Piedmont Catawba tribes in quite some time.

They were all rounded up by Virginia's Governor Spotswood, and sent

to Fort Christanna. Their numbers had been shrinking, and they needed

to band together to help them survive. They collective become known as "Saponi".

In the 1740s the government still

considered the Catawba a Nation, as opposed to the Settlement

Indians. Per Hudson, these settlement Indians were for the most part,

composed of Indian Nations that were quickly on the road to

extinction, passing first by the way of assimilation. He says; “The

settlement Indians consisted of Cheraws (Sara), Uchee's (Yuchi),

Pedees, Notchees (Natchez), Cape Fear and others. Governor James

Glenn stated in 1746 the Catawba had about 300 warriors. In 1743

Adair estimates the Catawba had abut 400 fighting men. Adair also

says the Catawba Nation consists of over 20 dialects, and he lists a

few of them – Katabhaw, Wateree, Eeno, Chewah, Chowan, Cangaree,

Nachee (Natchez), Yamassee, Coosah, etc. [36.]. The "Coosah" are Creek, and the Chowan are Shawnee, one of their most bitter enemies. When it was written some of these "dialects" couldn't understand each other, that is DEFINITELY true.

By 1760 the Catawba were a small

nation completely surrounded by White frontiersmen. Another small pox

epidemic in 1759 had killed half, once again, of the Catawba Nation.

In 1763 King Haiglar had been killed. In his place was elected

Colonel Ayers. Hudson suggests Ayers fell out of favor with the South

Carolina government, and Samuel Wyley, acting on behalf of South

Carolina Governor Bull, persuaded the Catawba to get rid of Ayers,

and they elected King Frow to take his place in 1765. The names of a

few of his headmen exist. They were Captain Thomson, John Chestnut,

and Wateree Jenny. By the turn of the Century, the Catawba no longer

mattered. They were few in number, surrounded by Scots-Irish settlers

who barely realized there were any Indians living in their midst.

[37.]

Map

14. Movements of some Catawban Bands, mid-18th

Century

Above

is a map showinig movements of most of the Eastern Siouan groups

between the times of De Soto and Pardo Pardo to the middle of the

18th century,

when many groups disappear from most historical records. It is taken

from 'Catawba and Neighboring Groups', by Blair A. Rudes, Thomas J.

Blumer, and J. Alan May, p. 302. This map does not show the movements

of the Northern branch of these Eastern Siouan groups.

These

groups were moving i.] towards the Catawba; or ii.] to be nearer

Charleston. Both moves appear to be for safety. They were afraid of

something in the interior. Was it just enemy Indians, or was it

something more sinister? Then during the Yamassee many turned on the

English near Charleston. Why? They were already very weak before the

Yamassee war. After the war they were broken, and were more like a

few refugee families scattered near their former homes. They would

linger for a few decades as separate bands, but after a time they

would have to assimilate, and lose their separate identites, to a

large degree. Only the Catawba would remain un-assimilated, but their

numbers too, would continue to decline.

Map

15. Deerhide Map

Above

we have another map from 'The Catawba Indians' by Brown. It is dated

about 1725. It too, is between pages 32 and 33. The map isn't

geographically accurate. At the southern end of the map is the city

of Charleston. At the Northeastern end is Virginia.

The northwestern end has the Cherokee, and beyond them the Chickasaw. Thee is a direct route from both Virginia and Charleston, South Carolina to Nasaw, which is cited as being the Catawba. They are at the center of the map, so perhaps the map was made by a Catawba.

The northwestern end has the Cherokee, and beyond them the Chickasaw. Thee is a direct route from both Virginia and Charleston, South Carolina to Nasaw, which is cited as being the Catawba. They are at the center of the map, so perhaps the map was made by a Catawba.

Between

the Catawba and Virginia is only one settlement – Saxapaha. It is

dated 1725 and seems be the same location as the Indians said to be

on Flatt River, in 1732.

The

Succa are between the Saxapaha and the Catawba. They have to be the

Sugaree. The Suteree are far closer to the Catawba, due east of them.

They must be the Shackori. To the south and much closer to Charleston

is Charra. To their north is Youchine. What is that? Without the 'n'

this becomes 'Youchie' – was there a small Yuchi/Euchee settlement

there? Wiapie is next closest to the Catawba. Is this Wiamea?

There

are four more communities to the South and west of the Catawba. There

is the easily recognized Wateree. Then we have the Wasnisa, Casuie,

and Nustie. Notice the 'Nisa' ending for Wasnisa. It is similar to

Nasaw. Is this the Waxhaw? The others, I can't figure out. Maybe

Congeree or Saponi? We know a band of the Saponi would move North of

the Catawba near Salisbury in 1729. They were said to have been

called "Nasaw" at times, too. Without further knowledge, I might never

figure them out.

Map

16. The Popple Map of 1733

There

are several maps between pages 32 and 33 in "The Catawba

Indians" by Douglass Summers Brown. This map, dated 1733, show

the locations of several bands at this time.

It

has the Keawee just to the north of the Saraw, who are on the north

side of the Pedee River. Downstream from them are the Pedee. The

Congaree are still on the map. To their north, in succession, are the Watarees, to their east the Sugaus, to their

northwest the Waxaus, then following northwards, the Sataree, and

Catapaw. So we see more Catawba communities than we previously had

seen, and hence his map needs to be included. Also notice there are

still some Yamassee around, in the southeastern portion of the map.

Please note the shrinking land base of these Indians.

Tutelo

to Canada With Six Natons

not finished <--> add later.

Map 17. Yamacraw Indians West of Savannah

War

with Spain;

War of Jenkins Ear 1739-1742

I

wish I could enlarge this picture , but when I do the writing is all

out of focus. I even tried getting a magnifying glass, and still

couldn't make anything out. But you can see the word “Yamacraw”

to the west of the brand new town of Savannah, which is the “square”

on the south side of the Savannah River hear its mouth. Oglethorpe

had founded the colony of Georgia in 1733 and this upset the Spanish

in Florida who claimed that land for Spain. A man named Jenkins

committted some kind of crime in Spanih Florida, and his punishment

was to have his ear amputated. This upset the English crown and a war

was declared. To make a long story short, in 1740 Oglethorpe beseiged

Fort Augustine, but failed to take the town. In 1742, the Spanish

beseiged Savannah, but failed to take it. In 1743, both Spain and

England attempted the invade the other, but both offensives failed.

In 1748 the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle was signed between England and

Spain. There was no change in borders, and the war in America was

pretty much declared a stalemant.

Http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/tomochichi-ca-1644-1739 Shortly I will explain why I bring up this conflict. There was a small Indian tribe in the vicinity of Savannah called the Yamacraw. The link above says “About 1728 Tomochichi created his own tribe of the Yamacraws from an assortment of Creek and Yamasee Indians. After the Yamassee War, there were few Yamassee Indians left alive. Small groups of a few families here and there united together. This group came together just to the south of the Catawba lands. I usspect the same occurred on Catawba lands. A few Indians here and there united under the names of some of the surviving bands. Perhaps the Pedee Indians are a result of a few survivors of several bands of the Catawba, as well.

The author calls Tomochichi an “aging warrior” and one is left to assume he might have taken part in the Yamassee The article states, “War twenty years earlier. Interestingly, Tomochichi asked john Wesley to teach his people about Christianity. After Oglethorpe returned to Georgia in February 1736, the chief received John Wesley, minister of Savannah, his brother Charles, and their friend Benjamin Ingham. Tomochichi reiterated his requests for Christian education for his tribe, but John Wesley rebuffed him with complex replies. Ingham, on the other hand, assisted in creating an Indian school at Irene, which opened in September 1736 much to the delight of the elderly chieftain.” He died October 5th, 1739. His tribe vanishes from history after his death.

By

this time the various Eastern Siouan Bands are being known as part of

the “Catawban Nation”. Many of the former bands are huttled

together along the North Carolina border with South Carolina to the

south of Charlotte, North Carolina. Another

grouping of Indians was further east along the Pedee River, who came

to be called “Pedee Indians,” and another further north we shall

talk about shortly, who are still being called Saponi Indians, even

at this late date.

After

these wars there just weren't enough Piedmont Indians left to benefit

the wealthy Charles Town merchants anymore. From about 1720 trade on

in Indian slaves declined, and trade in African slaves grew. With

Indian numbers declining, and the number of mimigrants on previous

Indians growing, the tables had turned. There were now more settlers

than Indians. I'd like to be able to say that with more and more

people, they could no longer enslave free Indians without more and

more people realizing the inhumane brutality of the practice. However

the treatment of African slaves makes that argument pretty lame. We

have to conclude that the Indian population simply had died off. Here

was no one left here to enslave.

No comments:

Post a Comment